On parental leave at early stage startups

Becoming a new parent has been one of the wildest experiences I’ve ever gone through. When many folks go through it (myself included), not only is there the stress of how to take care of a new human, but also how much time to take away from building.

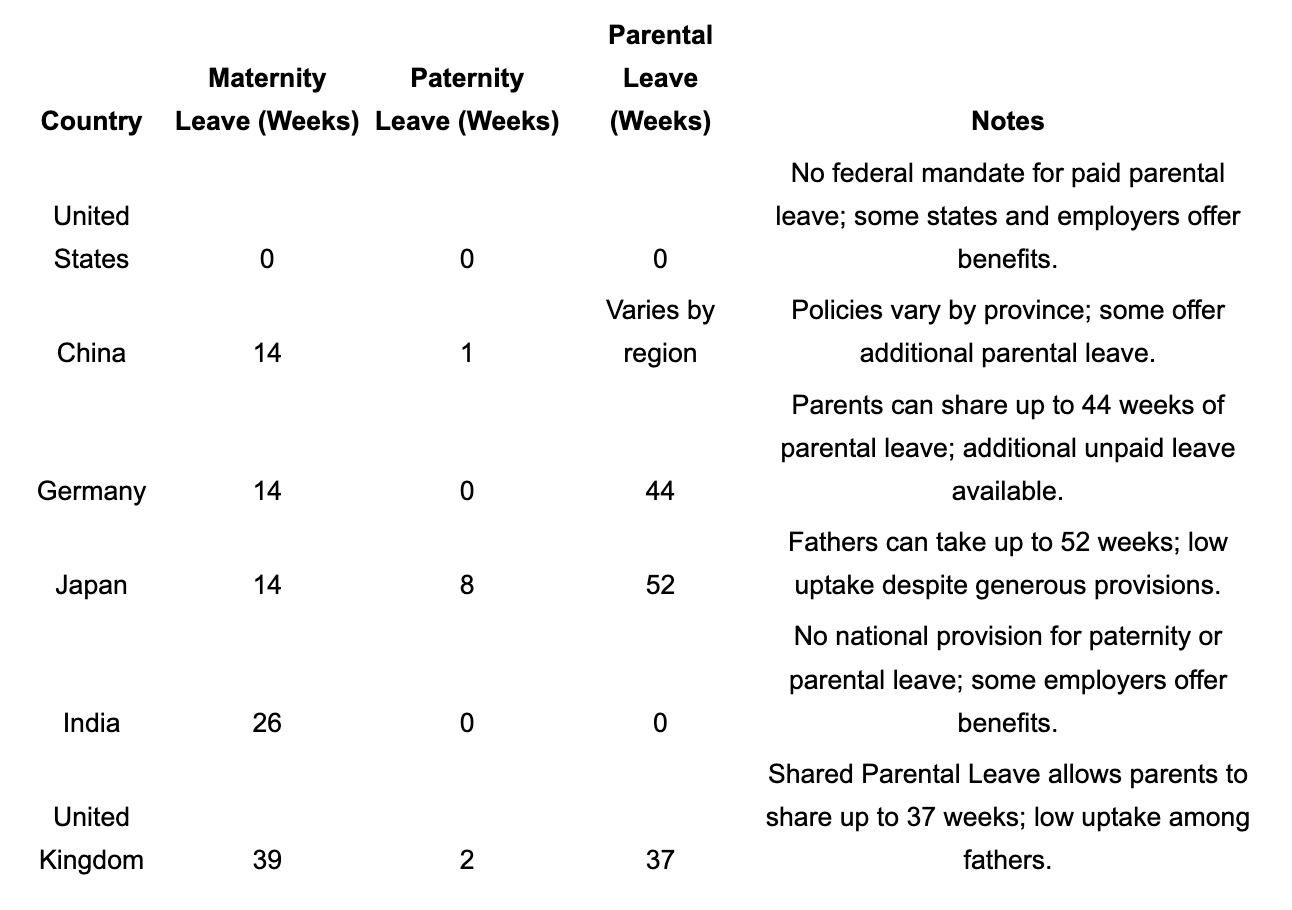

When it comes to parental leave, it’s no secret that the United States lags significantly behind other developed nations. In many countries, generous parental leave policies are the norm which creates social expectations. For instance, countries like Sweden offer up to 16 months of shared parental leave, while in Canada, new parents can receive up to 18 months of leave. Here’s a bit more data from a few countries:

The U.S. is one of the few countries without a federally mandated paid parental leave policy, leaving companies and/or states to create their own policies or rely on unpaid leave through the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

There’s no clear answer to what the right amount of time to take off is, and there’s unique social pressure that surrounds that question.

The unique challenge for early stage companies

Going from 0 to 1 is a particularly hard challenge. Amongst all the questions one has to answer, parental leave is often not the highest priority. Early stage companies operate on tight budgets, lean teams, and with high expectations.

What makes this even more challenging:

- When you raise venture capital, the opportunity exists within a window, and time away has a high opportunity cost.

- Early stage companies bias younger and more male, so you may be the first person at your company to take leave or have a unique perspective, literally writing the rules and setting a precedent.

- Days at an early stage company equate to weeks at later stage or public companies.

All of that makes parental leave feel like a challenging or even impossible benefit to consider. In my years building startups and in technology, I think that sentiment has changed, but the reality has not. In other words, we may be much more empathetic, but that doesn’t make it less challenging to determine what kind of benefits to offer or what to ask for, especially in the context of earlier stage companies.

So what do we end up doing? We try to be empathetic by not rocking the boat – we treat parental leave a lot like we treat vacation. We try to be a team player, looking to strike the balance between what feels “fair” and what feels necessary.

However, it isn’t analogous to vacation, and it’s an impossible (and sometimes contentious) negotiation that leaves every side feeling like the outcome might be suboptimal for everyone.

Ways to design parental leave

There’s clearly no right answer here, and there are lots of sides to this argument. It gets easier as organizations become more stable (> 20 employees, some PMF) and resilient to key team members taking time away, and the benefits are clear:

- Better retention

- Easier to attract talent

- Stronger culture

However, at the early stage when a company is pushing towards PMF, those things, broadly, matter less. Ideally there is federal precedent in the future that sets expectations for everyone, but in lieu of that, this remains a complicated subject.

We know that a few months of parental leave is beneficial for everyone (less depression, fewer complications, better outcomes for the child). It’s instructive to internalize the research, but we know that much of it is done in populations associated with larger businesses and outside of the context of early stage company building.

There are several stakeholders to consider here:

- The business

- You and your family

- The child

Moreover, each circumstance is different and deeply personal, e.g. support that exists around you, complications during or after birth, cultural expectations, the current state of the business, and more.

For early stage companies, each stakeholder matters and seeking some compromise that maximizes for everyone is reasonable. In “cycles” of 24 months (the typical runway between rounds, although that’s getting longer), it’s often impossible to offer several months of paid time off without material impact to the business.

How much leave is “enough”?

The answer depends on a lot of factors, including:

- Who the person is: The impact and recovery time for the birthing parent vs. the non-birthing parent are quite different.

- Health of parent and child: Complications during or after birth can extend recovery time and the need for additional support.

- Support network: Parents with strong family and community networks may find they need less time off, as they have people to rely on for help.

- Nature of the role: The intensity and flexibility of a job can make a big difference; however, at early stage companies every person is often indispensable.

- Business context: The health of the business certainly influences what it can tolerate.

As a person designing internal policy it’s hard, if not impossible, to be aware or empathetic to all of those circumstances. Therefore, you have two choices:

- Figure it out when it happens

- Design something that sets expectations

We’ve talked a bit about the former – this is often what folks do and leads to negotiations that create suboptimal outcomes for everyone.

I’d advocate for the latter, and opt for policy that is designed conservatively, then allow your team to self-regulate.

Why I found 3 weeks to be valuable, and why I’m in favor of up to 3 months

As I said above, I have a lot of advantages: I live in a progressive state, and I have a lot of agency over designing my own company policy and how I work. Moreover, I am a non-birthing parent, and my wife is able to take 3 months off while I begin to work again.

Not everyone is in this position nor has the same set of circumstances.

Given my situation, I found 3 weeks totally focused on my family’s wellbeing after my son was born to be the right amount of time to adjust to our new world, and away from building.

However, I don’t think that’s a good rule.

Given the research around this & the context of early stage building, I think offering up to 3 months of paid time off is right. Research shows that leave in that period promotes:

- Improved mental health for parents: There are significantly lower rates of postpartum depression and anxiety, especially among mothers (Bullinger, Journal of Health Economics, 2019).

- Better emotional and behavioral health for children: Early parental bonding results in better attachment, leading to improved emotional regulation and fewer behavioral issues in childhood and adolescence (Mikulincer & Shaver, Attachment Theory, 2020).

- Enhanced cognitive development: Children show improved early brain activity patterns, indicating stronger cognitive function; these children often perform better academically, as shown in EEG studies and findings from longitudinal research (Child Development, Brito et al., 2021).

Moreover, I firmly believe that those that choose to operate in early stage businesses tend to self-regulate and are internally motivated. They are hyper aware of business context, and are motivated to design a balance that works for their family and to push the company forward.

Ultimately, there’s more upside to creating an environment that maximizes flexibility and support and a culture that allows each parent to decide what’s right for them, than there is to being overly restrictive. It’s better for business – creating more near- and long-term loyalty, more balanced employees - and simply better for new families.