Five years of building

In March 2020, I left the company I co-founded in 2015. Building start-ups is tough - they require a level of self-sacrifice and commitment that few other things do. They also return in spades, both personally and professionally - I learned more about myself, collaborating with and managing people, building products, and business in the last 5 years than any other period in my life.

There are many reflections on building startups across the internet, so I’ll simply focus on a few areas I have learned a great deal about.

The overarching lessons can be summarized as:

- The market always wins, so choose a big one. Even if you have a great product and team, a small market will result in a subpar result.

- Don’t professionalize your business too soon - maintain flexibility until product-market fit is extremely obvious.

We felt the fastest way to get to product-market fit was to have a sales-focused culture to inform our product decisions. While that meant we arrived at paying customers sooner, we were not precise enough in who we were building for, which resulted in decisions that were expensive to recover from later on.

More detail below. Whenever I refer to “we”, I’m referring to myself and Fynn (my co-founder).

Building SMB products

We started Matcha with a few insights - 1) social channels were increasing in influence as a channel for commerce, 2) the cost of traditional advertising was rising rapidly, and 3) the customer increasingly preferred experiences over product. SMBs struggled to address these market realities because content, what every social channel requires, was still very expensive.

Those three basic insights informed our thesis to democratize access to content for SMBs in order for them to compete digitally, and informed nearly all of our business decisions.

In 2015, the fundraising environment was good but cautious - there was talk of a funding bubble. In the Southeast, our activation energy was even higher because potential investors were keen on traction before investing. That forced our business to be sales driven, so we forward sold our vision and prioritized product velocity to get to market as quickly as possible.

We built an organization driven by customer intimacy, focused on turning insight from the market into product features and services that created business value quickly. The first version of our product was built for the most part in 6 months, partially outsourced, and not 100% stable - that version, along with the services we sold around it, quickly gained dozens of customers and the traction we needed to raise seed capital.

We built broadly across the trends we were seeing and for the customers who were buying from us - a content marketplace to solve the supply problem, direct posting/scheduling for social platforms to solve distribution, integrations into CMSes like Wordpress, and our own analytics pipeline using Snowplow for more precise measurement and attribution. We also built professional services to augment the product, such as custom content, media buying, and video. The net effect was a market that bought easily from us, but for a variety of reasons, and a team that was stretched thin across too many shallow features.

Our pricing at launch averaged $1,500 per month, which we found initial success at and reached ~$100K in MRR in 18 months. That enabled us to raise additional capital on the back of our software/services model and professionalize our go-to market to really attack the opportunity.

Over time, the $1,500 price point limited our total addressable market (TAM) — there simply were not that many SMB deers in the verticals we were targeting. Therefore we shifted our strategy towards hunting rabbits (< $1K per year) — which we found many more of. Unsurprisingly at that price point the market’s expectations were different, so we shifted the entire go-to market strategy from inside sales-led to product-led - it was an enormous, painful lift to change the DNA of the organization from customer intimacy to product-led, but appears to be the right direction for the company now.

These are some of the hard lessons I learned over the years building for SMB companies:

- SMBs expect low prices and short commitments, which requires an extremely high velocity inside sales motion (but that’s usually impractical or too expensive) or a product-led sales motion. As soon as we reduced price and decreased contract periods, we saw increased sales velocity, but that exposed a very real churn problem, too.

- Long contract periods are great for cash flow, but they artificially hide gaps in product value. In the SMB market, getting feedback quickly is really valuable so shorter contract periods are useful.

- Pricing and packaging are hard, but you’re partially in control for how hard it is. There are two types of pressure when building them - internal (what the business can bear from a GM perspective) and external (what the market will accept). As an organization professionalizes, the internal pressures increase substantially - especially for SMB products which move at a high product velocity, maintain as much internal flexibility as possible until you don’t feel as much external pressure to change pricing materially. We professionalized the sales team too early, which limited our internal flexibility and prolonged necessary changes to go-to market.

- Outsourcing product value gets you to market sooner (which is important in SMB), but don’t outsource core product value that gates growth (or be sure to anticipate any friction in that dependency). We relied heavily on external partners to supply our content marketplace, and they were slower than anticipated to deliver. It’s hard to quantify the impact of that, but it was certainly one factor in customer acquisition and churn that was hard to ungate without relying on them.

- Verticalization is a great go-to market tactic to gain early traction in the SMB, but don’t overfit the organization or the product. Build product value and perceived value that can extend horizontally when needed - it will be harder (for some products, much harder) than you anticipate to expand horizontally. For example, our team and core product value was overfit for the outdoors industry, and it was costly to change that (both in finding new team members and in expanding the product value).

- When you provide professional services to the market, they should only serve to increase adoption of your product or create a barrier to exit, not serve as core product value. We offered media services outside of our software, which filled a need (and drove decent revenue), but over time we weren’t sure if a customer bought because they wanted software or an agency - those in the latter camp churned hard.

- Build the product as narrowly as possible (or, in other words, solve for the narrowest pain you can find). If you are truly a first mover / category creator, know that will be an expensive path both in product development and brand building, but most businesses are not.

Selling / Marketing

Our product thesis wasn’t new - the problem had been talked about with a lot of hype at the enterprise level, with some companies raising in excess of $100M to attack variations of the problem. Therefore, we didn’t think we were re-inventing the product wheel. Instead, we perceived innovating in sales and marketing to sell into the SMB was the core challenge. We were partially right -- SMBs are hard to sell to, especially when you’re selling marketing technology —, but we initially focused too heavily on distribution in lieu of product and positioning.

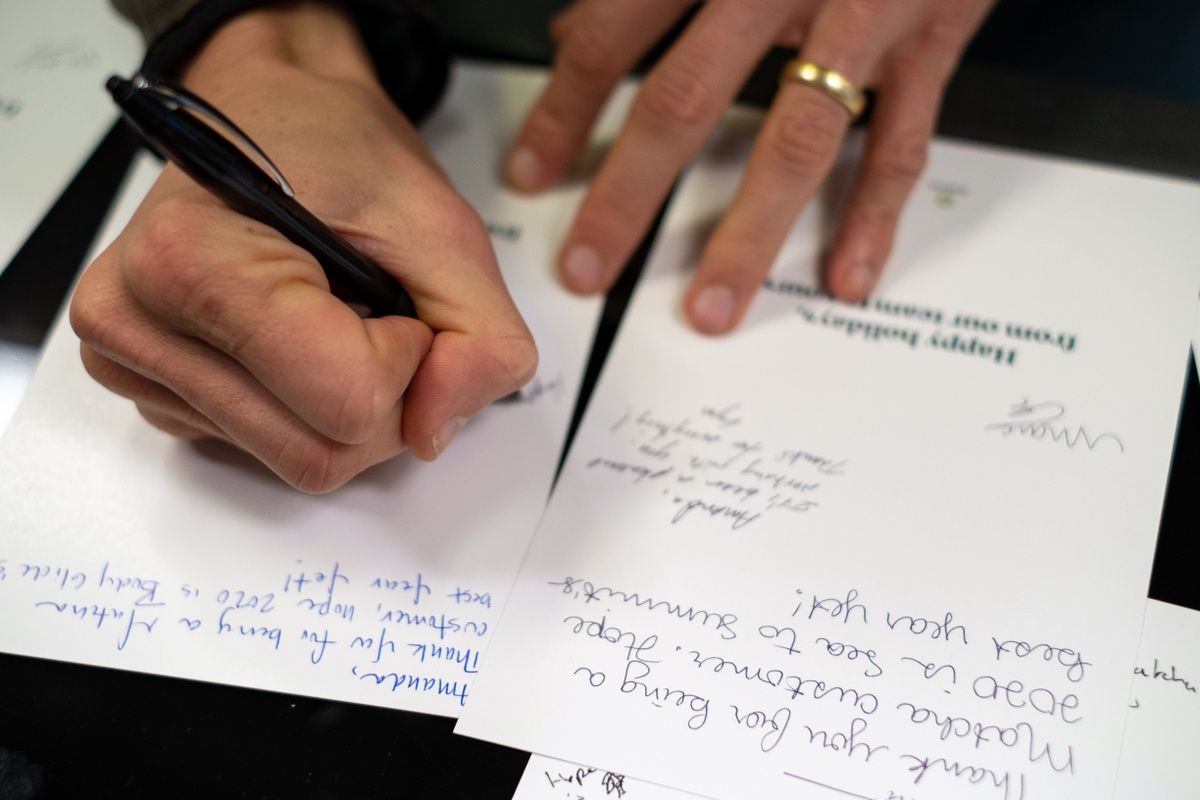

To gain initial traction, we spent a lot of time at trade shows in our first vertical, essentially doing field sales. This was a good move because our initial industry was relationship-driven, and it allowed us to become extremely intimate with our customers and their problems. The secondary effect was those relationships created a set of early, forgiving customers that we could safely iterate with.

Up until $100K in MRR, we focused almost exclusively on revenue growth rather than overly controlling gross margin or worrying about scalability. Once we crossed that threshold, we started to really look closely at our sales motion and profitability. We transitioned our sales motion from field sales to inside sales to decrease our cost of acquisition, and we tightened our service delivery to improve our gross margin.

After our Series A we perceived both market validation and validation from sources of capital, which prematurely convinced us we had enough product-market fit to focus on professionalizing our sales motion to scale revenue. We grew our sales team from 5 people to 15, nearly half of the company, and hired managers to handle success, marketing, and sales.

Professionalizing sales and support created a couple of problems - 1) it effectively abstracted us — as the founders -- from our customers, and 2) it decreased internal flexibility to adapt our business model as we learned new things from the market. To make #2 tangible, we could not decrease the price of the product to below $200 per month at a 60% gross margin because the cost of acquisition in an inside sales model eats any profit.

As we learned more from the market, we were faced with the reality that while we had sold to hundreds of customers, many of them were not fanatical about the product nor was our sales velocity repeatable (lots of variability in quota attainment). That forced us to reconsider how much product-market fit we actually had and refocus our resources from distribution to product development to create a much more compelling product at more appropriate price points.

These are some of the other hard lessons I learned on S&M:

- Professionalizing a sales motion too early can kill products and businesses. Once you professionalize, there are real constraints on both pricing and packaging, as well as go-to market.

- While it may work in some cases, SMBs increasingly prefer to come to you rather than you going to them (e.g. cold calling). SMBs will continue to demand easy to try products where they can control the sales cycle.

- There are several core platforms that SMBs (especially in eCommerce) are building around, for example Shopify. Your product has to play nice with them, and there’s a real distribution advantage of gaining mindshare in their marketplaces.

- The market always wins, no matter how good your operations are. Sell into the biggest market you can possibly find - it makes product and distribution challenges easier to iterate on. We spent too much time innovating how we distributed our product for a small market, which led to a sophisticated sales process/team without an opportunity to win big.

- At an early stage in the SMB space, I believe product development and ecosystem/partner marketing should be the #1 focus.

Building organizations

Managing people was the hardest part of business building for me to master. We grew our headcount from 0 to 50 people, with the majority of headcount growth between 2018 and 2020.

At an early stage, the company was primarily made up of young talent that were not specialized. Our team was comfortable operating across functions, and they built generalist skill sets. The flexibility in their roles was key in allowing us to shift product and go to market focus as we needed to, and many of them developed into great, specialized individual contributors later on.

Much of the early years helped us establish both our leadership styles, which turned out to be very complementary, and the company’s culture, which we solidified shortly after we raised our seed round. Formalizing our values and our mission were important levers as we built the company. Furthermore, making them a consistent part of our review processes and our internal wikis pushed the team to judge themselves and others by them, creating a level of objectivity we could use to help each other improve.

As we grew beyond 25 people, we sensed a level of disorganization and discontent from folks so we began adding organizational structure to give people clarity and guide their work (this essay from A16Z was a useful framework). We found that work began to be disjointed and silo’d by functional area and we were still at a stage where we needed everyone to be on fire about the same thing, so we implemented OKRs (There are a ton of resources about OKRs, and this book does a nice job exploring them). That simple goal setting tool was essential in creating a great deal of alignment, and variations were used throughout the succeeding years.

After we raised our first institutional round of financing, we sought to hire quickly to accelerate growth. We successfully hired leaders away from some of our market’s top startups and felt like we had all the right people in the room. Unfortunately, that’s when we ran into challenges with TAM and consistency around selling.

We made a few wrong turns here - 1) we continued to hire to create an aura of growth, 2) we held on to bad revenue that perpetuated the misalignment of our resources, and 3) instead of recognizing the product-market fit challenges, we kept pushing a go-to market strategy that was inappropriate for the market.

At the time, we thought we could optimize ourselves out of the situation and then continue to grow, thus making our hiring proactive. That ended up being incorrect, and we were forced to reorganize a smaller company around the core functions we actually needed to correct our product-market fit issues.

The next time I build an organization, here are a few other things I’ll keep in mind:

- Defining culture and a strong benefits package early in a company’s life is extremely useful - both scale with the company, and are much harder to implement or change later on. For instance, going from 60% healthcare cost coverage to 100% has an enormous impact on your pro forma.

- Have a clear product and company vision that is communicated often, even if it may change — when people can see for miles, they tend to operate more creatively and autonomously. We did this through a combination of regular company memos, all hands, and OKR check-ins.

- Until there is obvious product-market fit, optimize for low organizational friction over everything else. We held on to revenue we knew was misaligned with our product vision for way too long, and that created costs across the organization from product to support.

- Be opinionated in hiring - especially early on, don’t be afraid to build a homogenous group if it’s highly effective and aligns with core cultural values. The hiring pool will broaden later on, and if the early folks are excellent they will hire excellence.

- Use OKRs (and other tools) to control organizational output and create accountability. Without some form of structure like OKRs, you may lose focus across the organization.

Company building outside of tech hubs

I have lived in Seattle and San Francisco, so building a business in Chattanooga, TN (and, later, Atlanta, GA) was a stark contrast. There are very real constraints to building a business in smaller markets (basically everywhere but San Francisco and New York), particularly access to capital and talent. The former hurts early on because the capital is much more demanding than on the coasts - we had to demonstrate real traction and low burn to interest any angel or seed stage investor. The latter hurt later on as we tried to hire and grow the business.

As first time founders, we also lacked really strong perspectives on building a business, and we didn’t have local peers that could guide us. One of the best decisions we made was to attend Harrison Metal’s General Management. That 3 day class gave us the basic tools and confidence to operate. Over the years, we also utilized some key frameworks to drive consistency and alignment across everyone we hired (e.g. the Minto pyramid principle for communication, and OKRs).

In addition to that course, we consumed as much content as possible from folks such as Suster, Lemkin, and Tunguz. Those folks helped us mature quicker than we would have purely through experience, and influenced how we hired, fired, built our mission and values, and so on. However their advice wasn’t always relevant given the inherent constraints in the Southeast. For instance, firing fast, while generally good advice, needed to be a bit more forgiving in Atlanta, where simply hiring someone else that is both functionally competent and has prior experience was not always practical over developing the talent we had.

While VC-backed startups in non-tech hubs live by similar measures, they are not the same types of businesses that their peers are in tech hubs - the majority are lower growth, lower burn, and often built for smaller returns. We learned this over time, and adjusted how we operated to fit that reality.

I didn’t (and still don’t) view this as a bad thing - a ton of innovation happens in that structure -, and it doesn’t preclude some to be hyper-scale, IPO-worthy businesses (the proportion is just much, much smaller).

There are plenty of fantastic things about building outside of SF and NY, as well: higher quality of life, better work-life balance, rich regional cultures, lower salaries and rent, access to much more diverse talent/communities, plenty of Fortune 1000 companies to beta with (if you’re aiming at the enterprise), and great Southern food :).

----

Thanks to Fynn Glover for reviewing drafts of this.